Interview with Matt Lamont

Documenting the History of Graphic Design

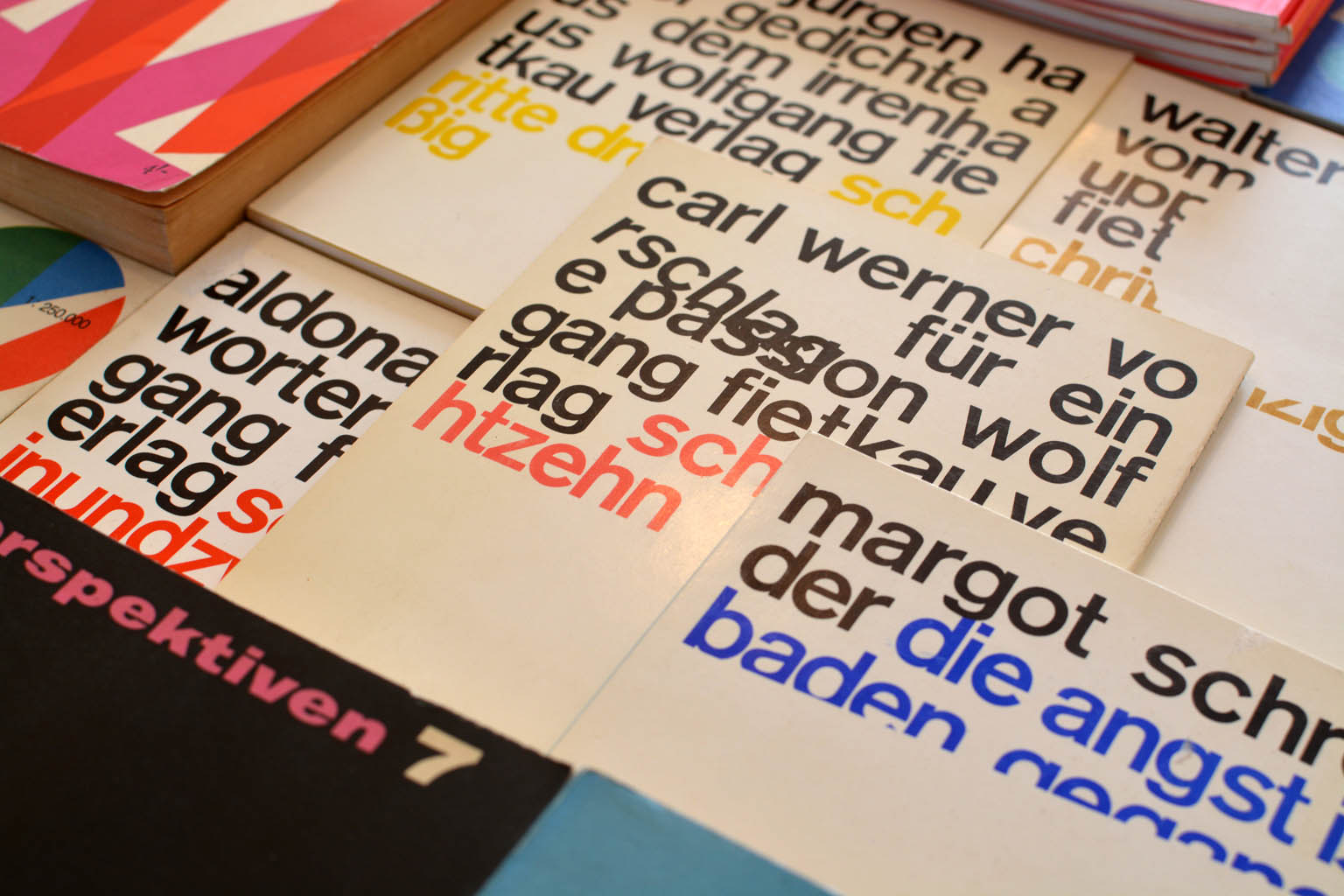

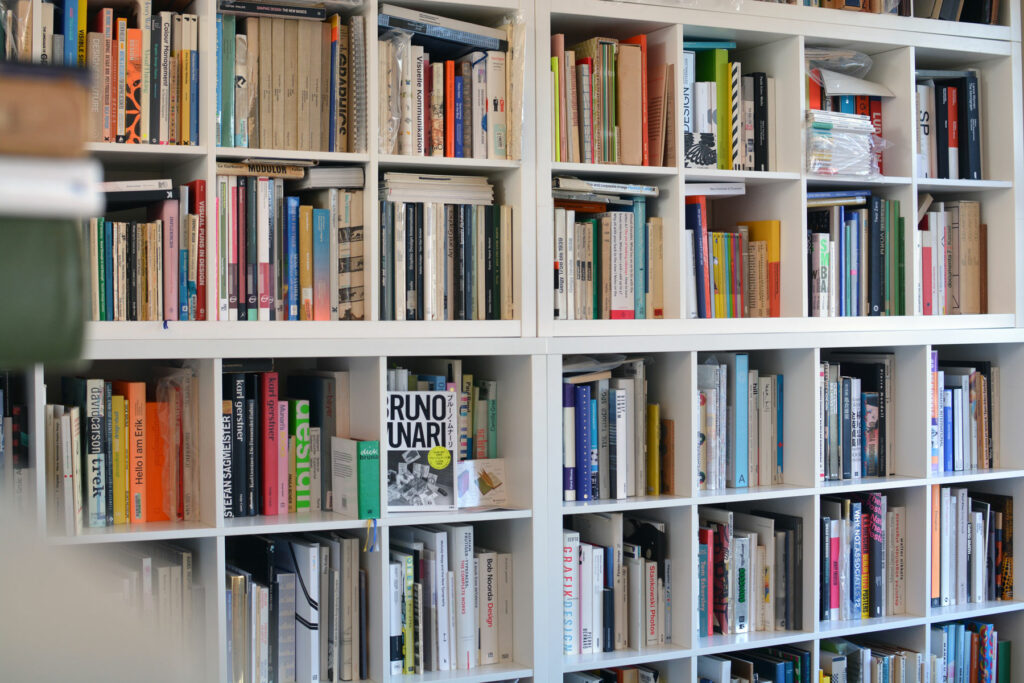

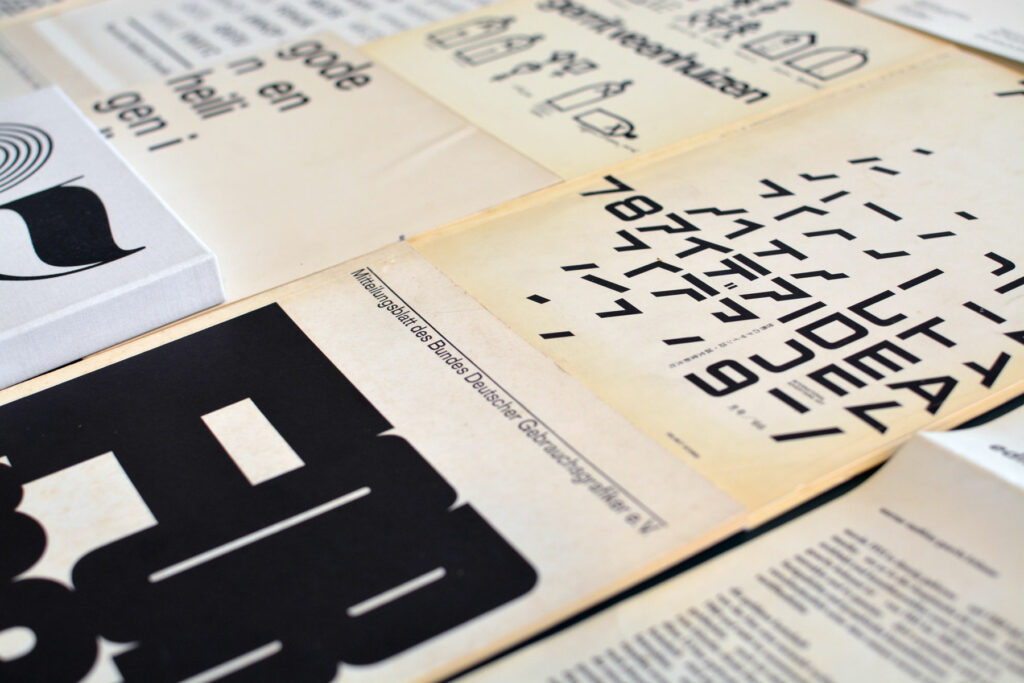

Matt Lamont has spent over a decade amassing a collection of printed materials. Design Reviewed is his personal endeavour dedicated to digitally preserving the rich tapestry of graphic design history and documenting the expansive visual culture of the last century. With a personal archive boasting more than 5,000 design artefacts, he uses this treasure trove for educational workshops, as a wellspring of inspiration, and as a means to deepen his understanding of design.

Martin: We met for the first time in 2013 at the BCNMCR in Manchester. I remember that you were collecting graphic design already back then. Do you remember that time? What were you collecting? How did you become interested in collecting?

Matt: I graduated in 2011 and throughout the following few years I collected design books mostly on theory and current trends, many Gestalten and Victionary published titles.

A lot of the books I was buying in the following years were first found on Flickr groups and albums, they were books released by ABC Verlag, monographs of designers such as Karl Gerstner and Max Bill and many of the recommended books that focused on design movements and periods.

During this time, it was easier to buy rare books as they often appeared on online auctions with little competition on bids and there were lots of sellers and websites online which were local bookshops and many of the stock was uncatalogued online, so you could have a good dig online to find books, it became a bit of a fun task to try to find them at the best price.

I have now collected an array of printed matter produced in the last 150 years and what began as a recurring hobby to source material for visual research, nourishment and further study, became a primary obsession of collecting and sourcing out-of-print books, mid-century magazines and exhibition catalogues from around the world.

This vast collection is currently housed at my place of work, (Out of Place Studio at Assembly Bradford, UK), and has been expanding year after year, rare and common finds archived blending a combination of personal interest and a desire to further my design exploration.

The majority of my archive represents designers from Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and Japan. And although 5,000 artifacts sound like an excessive number, especially when you think of the space required to house a collection of this volume, it represents a fraction of graphic design history. And I’m not stopping anytime soon!

Your collection and the digitization of it is such a valuable source for graphic designers who forget how rich our history is. We are often under the false impression that everything new solves an old problem and is therefore better than what we had before. Especially when it comes to tech inventions. In lots of ways today’s top notch software limits our creativity. We can easily reproduce the rectangular grids of Josef Müller-Brockmann, but the moment he rotates them or even makes them circular it becomes very hard for us with the tools we have. I would even argue that we wouldn’t have come up with the idea, because the tools we use, shape the way we think. Did you make that observation too?

Great design solves a company or individual’s problems or helps them reach goals or targets, although modern and new design can rectify these, especially in a digital space, creating design systems, cross-platform marketing collateral and influential design can date back decades, you only have to look at mid-century European modernism to be inspired and educated in communicating complex messages and designing inclusive campaigns through reduction, clarity of form and decisions on format and typographic decision making.

There’s a certain level of design thinking which is not utilised when we depend on tools rather than intellectual thought, intuition and creativity. Although the tools we use today produce some fascinating output and make designing complex perspectives and variations easy, we are often trying to recreate or reflect design from the past (in my opinion).

Luckily, when producing my own design solutions, my mind is full of creative solutions that pre-date the computer age. When looking through design from previous decades the formulation of new solutions, in particular, bespoke solutions is far easier to achieve without the imitation and following of trends and styles we find on portfolio websites. We can get hooked on trying to create solutions that get likes and online reach but the best design goes unnoticed, we should strive for subtlety and integration in our environment and the solution rather than the hype!

It excites me to see an increase in young designers’ interests in design history and design ephemera, it seems a shame that a lot of the historical matter taught in higher education is increasingly cut from courses or overlooked as non-essential. As part of my work with the archive I educate students on design history using hundreds of real example for a complete interactive and tactile experience. My workshops help students interact with the past, create discourse through visual matter and create integrity and awareness for young (and old) designers.

I wish Design Reviewed would have existed when I did the historical research for my doctoral dissertation about historic visual systems. Most of the material I found was from either Switzerland or Germany. I had to expand my research to type design to find older sources from more countries. You found so many more examples of systemic approaches in graphic design. Can you talk a bit about your findings? Are there systemic approaches in every country? Did this approach become popular everywhere at the same time?

A system of design exists in everything we see, from the natural structure of leaves to the architectural plans of cities. I find myself fascinated by the systems created in the tilework of religious buildings and find myself mentally dissecting design to try and think of the structures that create the form

But from a purely graphic design standpoint, most of my findings of successful systems stem from Germany and Switzerland. Although most of my collected design is from these two countries, Germany and Switzerland in particular, have a fascinating design history, the more I have researched the more designers and examples of their work I unfold.

Through my recent collecting and curating, I have found that mid-century Japanese design features many design systems, and it’s an area I have only started to research as I have collected magazines from the era over the last few years.

Just recently you shared with me a couple of beautiful examples of historic flexible visual systems. Can you share and explain them here?

There’s so many examples I could include but a few of my favourites include the following:

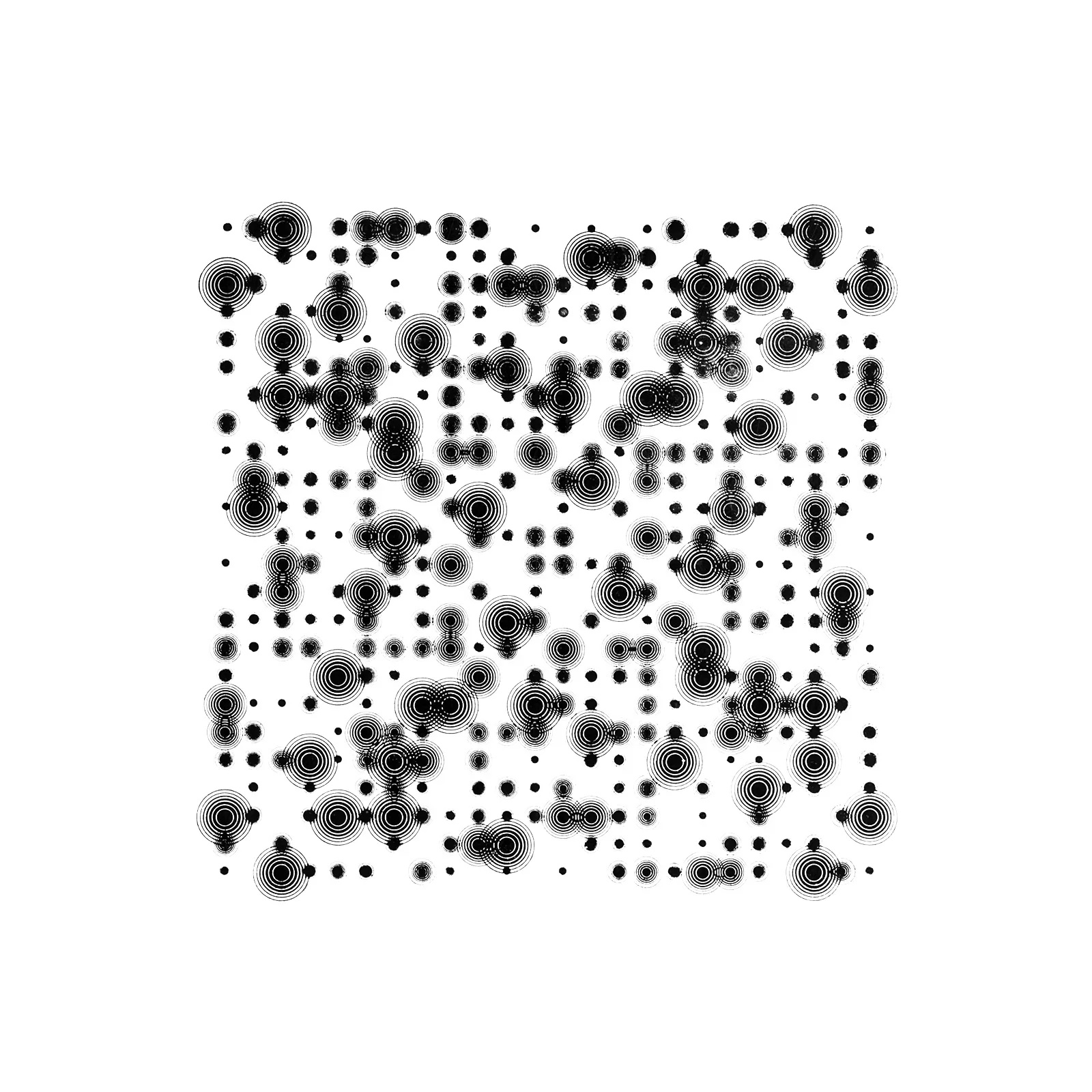

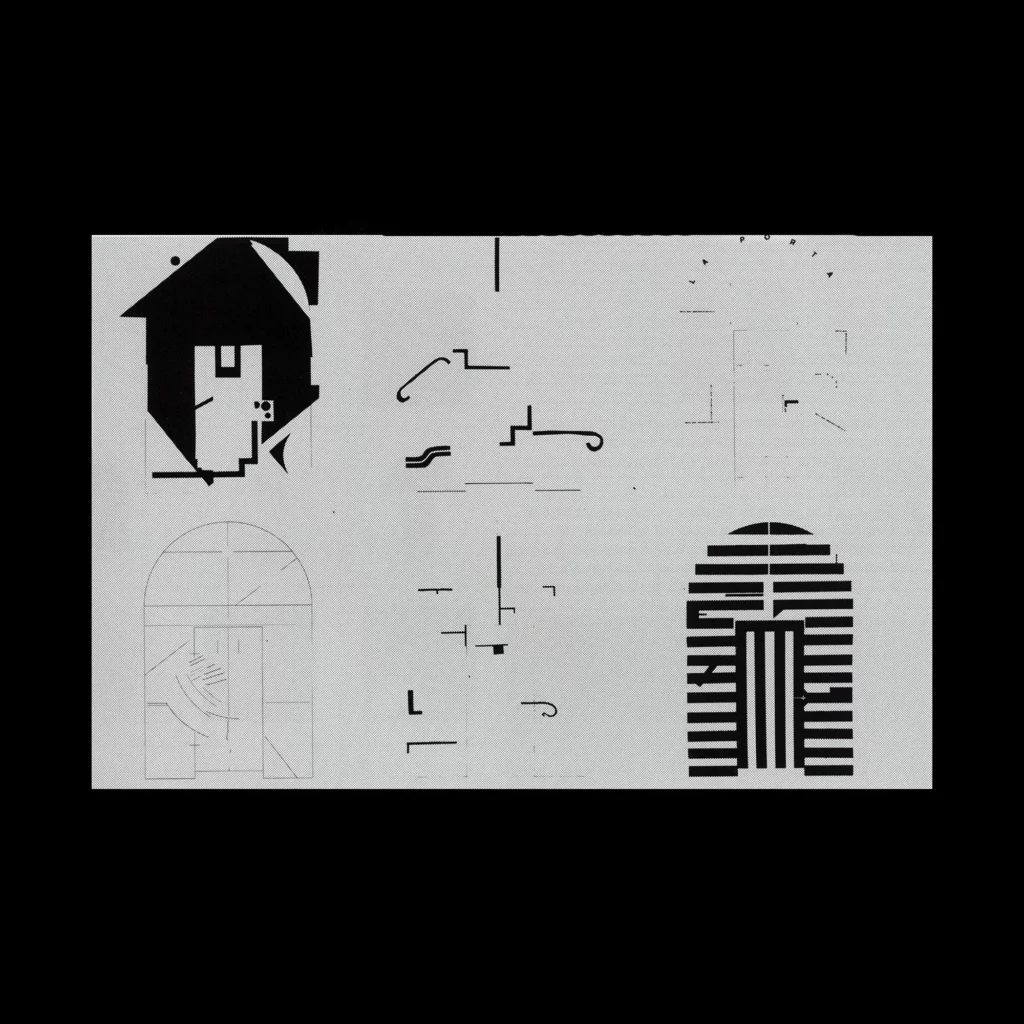

Kōhei Sugiura’s Design Systems for the 1964 issues of Design

In 1964, Sugiura was commissioned by the magazine Design to design each of their twelve monthly cover designs. Creating a series of systems which set the foundations for the design.

The May issues features a grid arrangement based on a 12×12 grid of 144 sections. The patterns are arranged at random at each intersection with a total of sixteen different graduations of sizes.

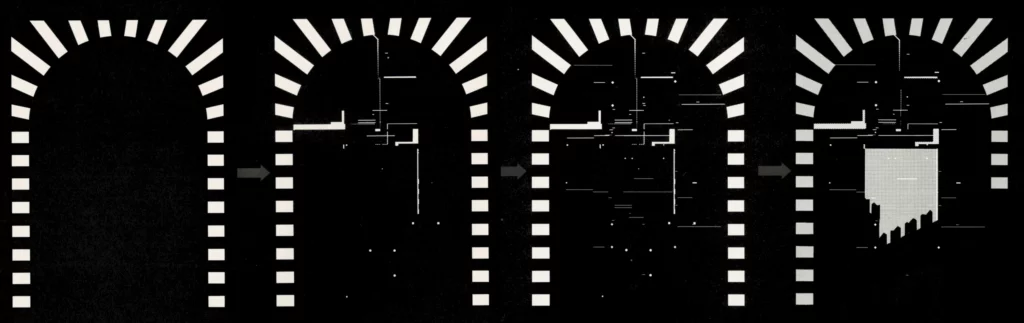

Design, June 1964

The June issue features a grid arrangement based on a 24×24 grid of 576 sections.

Ads in trade journals for Bayer, Leverkusen designed by Wolfgang Bäumer c. 1962-1964. Scanned from Gebrauchsgraphik, July 1966

Wolfgang Bäumer’s advertising design for Bayer has an adaptable design aesthetic alongside a skill of convening messaging through visuals. A fantastic example of mid-century German graphic design.

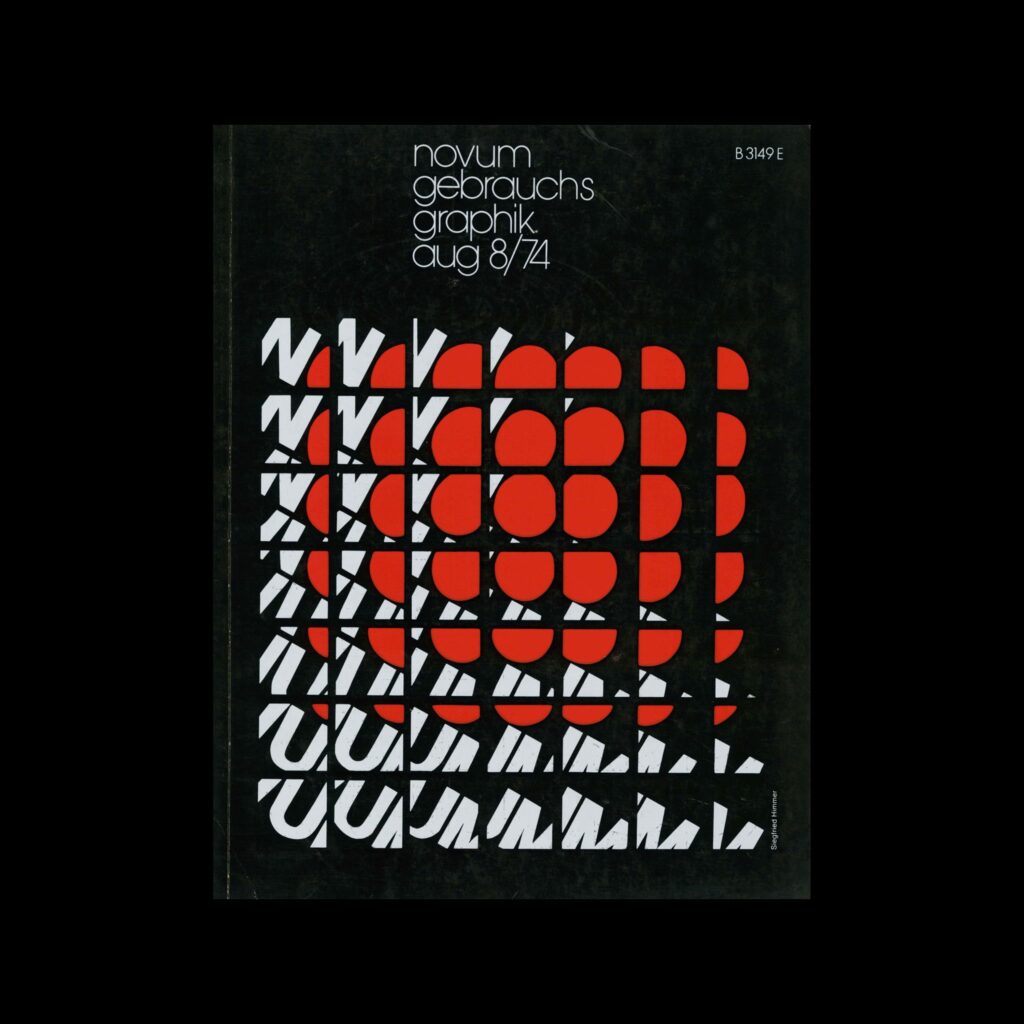

Novum Gebrauchsgraphik, 8, 1974.

Cover design by Siegried Himmer

Novum Gebrauchsgraphik was the relaunched magazine of Gebrauchsgraphik, which was first released in 1924. The magazine nearly ran for a century and each issue takes you through a visual journey of the time.

Novum Gebrauchsgraphik, 4, 1972

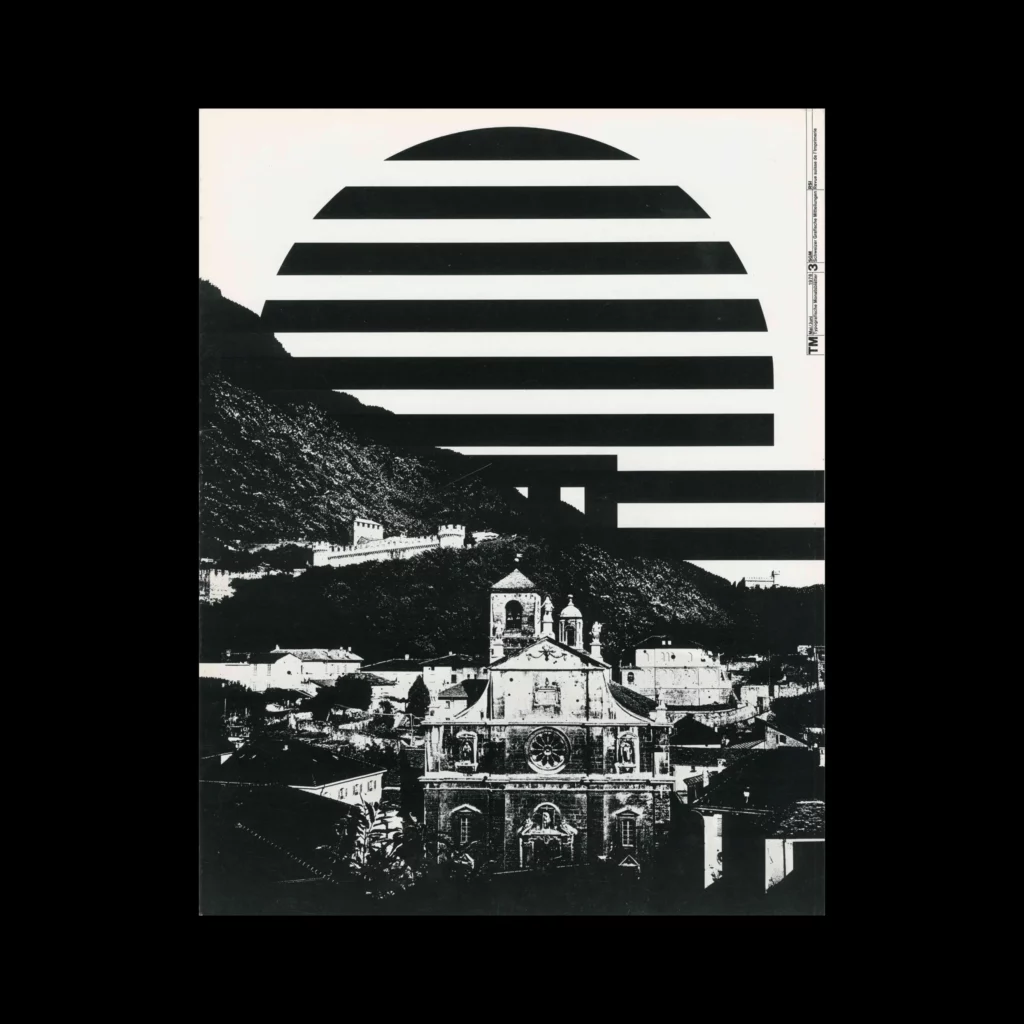

Gregory Vines’ Typographische Monatsblätter 1978 covers.

Weingart invited Gregory Vines to design the covers for the 1978 editions of Typographische Monatsblätter, a type-led Swiss journal, which documented graphic design for over seven decades. From the initial inspiration drawn from Bellinzona’s gate to the process of film montage, resulting in six stunning cover masterpieces.

What interests you in historic graphic design, that you lack in contemporary design?

I have a huge passion for documenting design which hasn’t been seen on the internet.

Current design primarily exists online, but there’s so much history that has not been scanned or documented yet!

Nothing beats stepping away from the digital noise, the fast creation of visuals, and the personalities of social media to enjoy the collated, curated pages of a century-old magazine. I feel contemporary design lacks a sense of social purpose and in an age where accessibility is paramount there’s a certain level of loss in originality. I am not sure if it is a sense of nostalgia and romanticism or a belief that midcentury design had perfected form and meaning, but I can’t help but look at designers in the 1960s to help inspire design solutions for today.

Thank you so much Matt for sharing your thoughts and archive with us. There is something very powerful in trying to slow down the creation-consumption-waste dynamics by reducing the digital noise, as you say name it. I think you inspired a few to pause and look for the new in the old.

Visit Matt’s brilliant digital archive at:

https://designreviewed.com